The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is one of 4 main ligaments holding the knee joint. It is the most commonly ruptured ligament in the knee, with a usual injury pattern of a sudden twisting on a fixed foot, landing awkwardly from a jump, or direct tackle. Patients often report hearing a ‘pop’ or something ‘going’ in the knee. Swelling is common within a few hours, and continuing playing is usually not possible at the time of injury.

Not all ACL ruptures require reconstruction, if instability is not a symptom, but each case is assessed individually. More recently, some ACL ruptures can be repaired directly in the early stages after injury, allowing a more rapid rehabilitation and avoidance of taking graft.

Link to BMI ACL experts Q and A

The diagnosis of an ACL rupture is made by taking a thorough history and performing certain tests on examination. The diagnosis should be confirmed by MRI scan, which will also show any additional injuries. Most commonly there may be meniscal tears or medial collateral ligament injuries.

Initial management of an ACL injury involves reducing swelling, regaining range of motion and retraining the thigh muscles. Every ACL injury should be managed individually. Not everyone with an ACL injury requires an ACL reconstruction operation. ACL reconstruction maybe required in individuals with symptoms of instability ( giving way), a feeling of ‘not trusting the knee’, or in young adolescents in whom it is known that further damage is likely if reconstruction is not undertaken.

The ACL is reconstructed using either the patient’s own hamstring tendons from the same leg, or the middle1/3rd of the patella tendon. The aims of reconstructive surgery are to restore static and dynamic stability, and restore as near normal anatomy as possible. This is achieved by using tissues from the patient’s own body to reconstruct the ACL, and then protecting the new ligament with a gradual rehabilitation programme with physiotherapy team.

Both pre-habilitation and post –operative rehabilitation are vital in recovering strength, range of motion and proprioception (the knee knowing where it is in space, and reacting to strains on it). Rehabilitation needs to concentrate on running, balance, jumping, landing and agility to prevent re-injury.

A general or spinal anaesthetic is required.

Surgery usually takes between 60 – 90 minutes depending on any associated injuries. An in –patient stay overnight is usually required although some patients do go home the same day. Physiotherapy begins whilst in hospital, and patients usually walk with crutches partial weight bearing for 2-3 weeks. This protocol maybe modified if additional procedures such as meniscal repair are performed.

Return to driving – depends on which leg is operated, but right leg surgery may require 4 – 6 weeks to regain sufficient strength.

When can I return to full sports? This is a very individual question, and it is often difficult to accept that it is usually a whole year before return to sports which require twisting, cutting and pivoting is possible. Some generalisations however include - Return to cycling – no sooner than 8 weeks post-operatively, and return to jogging no sooner than 3 months, to reduce strain on the graft whilst it is healing. Return to full sports should be no sooner than 9-12 months depending on recovery of the operated leg, but maybe up to 15-16 months. In short, the operated leg needs to have strength close to equal to that of the normal leg, prior to return to full activities. The rehabilitation, as discussed above, is paramount to regain those qualities needed to return safely to full activities.

Success rates – In general, the success rate following ACL reconstruction is 85-90%. The main long term risk is a re-rupture following a return to normal activities. The risk of re-rupture varies widely, between 2% - 25%, in various studies. The risk is age dependent ( approx. 15% < 18y.o. / approx.. ½ that risk in 18-25 y.o., and approx. 5% in patients> 25y.o. ) The risk of damaging the ACL in the other knee is a higher risk than re-rupture in an operated leg.

Long term consequences – 10-20 years after ACL injury, an average of 50% of patients will have some OA changes. There is however, a lack of evidence supporting a protective role of ACL reconstruction surgery against future OA.

Infection approx. 1 in 200 ( 0.5%)

Stiffness and swelling. Swelling will occur, and is managed with a cold compression device- a ‘cryocuff’, which patients take home. The cryocuff should be worn most of the time, except when doing exercises , for the 1st 3-4 weeks. It can then be used for periods each day, generally after dedicated exercises. Stiffness may present as difficulty getting full extension, but is less of a problem with ‘modern’ techniques of anatomical reconstructions, than it has been in the past. Very rarely further arthroscopy maybe required to release scar tissue, or blocks to extension that develop with healing.

Loosening of the graft - leading to further instability

Re-rupture of graft. This is the greatest long term risk and if it were to occur is most common in the first 6-9 months post-op. The risk is between 8-10% in most published reviewed series. If a graft loosens or re-ruptures then a revision ACL reconstruction can be performed if required in most cases

- Further arthroscopic surgery. Up to 30% of patients after ACL reconstruction have a further keyhole procedure within 10 years of the ACL operation.

- DVT /PE

- Damage to nerve or blood vessels. Slight numbness may be felt over the outside of the knee. This is usually temporary.

- Hard ware complications. Very rarely metalwork (staples or screws) may need to be removed at a later date.

- Hamstring problems. The donor site of the hamstrings maybe sore, and the healing can cause bruising. There can be approx. 10 % loss of power of flexion, which is not usually a problem.

MRI of normal ACL

MRI showing ruptured ACL

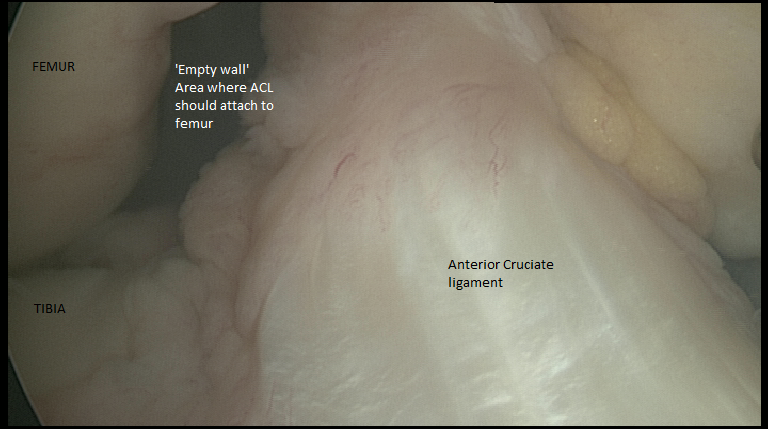

ACL reconstruction with graft in ‘sleeve’ of native remaing ACL to promote healing